ALT

ALTI must start by apologising for the long wait between drinks. December is always a gauntlet, and 2026 so far has continued the trend of the last two years in trying to kill me. As always, though, I have survived to keep thinking about animals.

Greenland sharks (Somniosus microcephalus) are the longest-living vertebrates that we’re aware of. Their lifespan is somewhere between 250 and 500 years. They are not the longest living organism. That title is shared among a number of species, some of which defy the the idea of the life cycle itself. Turritopsis dohrnii, a jellyfish, famously reverts back to its polyp state after their asexual reproductive stage, granting them functional immortality. They’re fascinating, but they don’t quite have the charisma of the Greenland shark, at least not to me. Their lack of brain streamlines their ability to live. It’s far more interesting to consider something that thinks, however simply, living for such a long time.

There are a few factors that inform the Greenland shark’s impressive lifespan. The first is size. Greenland sharks are big, some of the biggest sharks on the planet at 4-5m. The largest confirmed specimen of the Greenland shark is around the same size as the largest known specimen of the great white shark. The two species don’t live in the same places, so I can’t imagine they’d have cause to be insecure about one another. That’s the other factor: Greenland sharks like the cold, and they like the deep. They exist in the depths of the Arctic and northern Atlantic Oceans, where they swim very, very slowly through the dark waters. They’re sleeper sharks. Their movement speed tops out at around 70cm per second, or less than 3km/h. In contrast, the fastest known shark, the shortfin mako, has a top speed of 74 km/h. Mako sharks’ lives are significantly shorter than those of Greenland sharks, at only 30 years or so. The Greenland shark is wholly uncommitted to the “live fast, die young” lifestyle. Despite this, they’ve comfortably established themselves as apex predators. They eat whatever they can find, including seals, which is particularly strange because seals are much faster than sharks. We don’t know how the shark hunts them, we just know that they do. Once, a shark was found with an entire reindeer carcass in its belly. Another had parts of a horse. I can’t imagine the horse was running at the time.

Australia was colonised a little under 250 years ago. The United States declared independence just a few years later. There are certainly Greenland sharks that have been alive since before these events. This is, for me, the great appeal of organisms with exaggerated lifespans. It is easy to forget how short a period humans consider to be history. Evolutionary biologists estimate that Greenland sharks emerged as a distinct species between 1 and 2 million years ago. The Homo genus cultivated fire around the same time. Migration within and from Africa; the first civilisations; the rise and falls of innumerable empires. All the while, Greenland sharks cruised slowly at the bottom of the Atlantic.

Because they live so deep, Greenland sharks don’t have that much use for sight. This is lucky, because a small crustacean, Ommatokoita elongata, has a particular liking for the eyes of Greenland sharks. They latch on to the corneas, often resulting in blindness. The shark doesn’t seem to notice this; or if it does, it isn’t terribly bothered by it. Even if it was, what could it do? Sometimes successful evolution is learning to live with what happens to you.

you got games on your phone? (photograph by Franco Bafti via Getty Images).

Greenland sharks reach sexual maturity at around 150 years. That’s roughly a century past when humans undergo menopause. A Greenland shark that is currently on the cusp of sexual maturity would have been born at around the same time as Carl Jung and Albert Einstein. As far as I know, neither of them is considering getting pregnant at this point in time. A specimen born in the same year as the modern state of Israel won’t reach sexual maturity for another 70 years. Greenland sharks give birth to live young after carrying them for 8-18 years. A number of sharks demonstrate this ovoviviparity: their embryos develop inside of eggs, but the eggs stay inside the mother until birth. We’re not sure of how many pups are in a Greenland shark litter—some say up to ten, while others say around two hundred. That’s quite a difference.

Greenland shark meat is naturally poisonous to humans. It is rich in urea; and look, I’m not a chemist, but some Wikipedia perusal tells me that urea toxicity causes lethargy, cognitive decline, and sometimes death. The Icelandic have overcome this obstacle through fermentation, that proud tradition developed by countless communities in the Arctic regions. Hákarl, as the meat is called, is hung to dry for four to five months after the fermentation process. Even the shark’s meat moves slower than the rest of us. Hákarl is known as a highly acquired national dish; non-Nordics who taste it tend to have strong reactions. Anthony Bourdain notably hated it. The problem is taste extends to other parts of the meat, too. The slow rate of the Greenland shark’s life cycle is a major issue for sustainability. While the market for them as a food is niche, they’re often caught in industrial fishing nets by mistake. When a Greenland shark dies prematurely, it takes a long time for it to be replaced. Conservation works on a human timeframe, even when we’re engaging with other species. We’re limited by the decay of our own meat.

The Greenland shark has been written about in scientific literature since at least the late eighteenth century, but this certainly wasn’t the beginning of humans’ relationship with it. Traditional Inuit knowledge is famously comprehensive in its awareness of even rare and obscure species in the subarctic regions. Their legends on the Greenland shark concentrate on the shark’s association with urine, inspired by its urea permeating the general scent of piss. In one myth, an old woman was washing her hair with urine to cleanse it of parasites. She dried her hair with a damp cloth, which was caught by the wind and carried out to the ocean. The cloth became Skalugsuak, the first Greenland shark.

It’s difficult to estimate the life expectancy of humans throughout time. Part of this is due to lack of data; another factor is the issue of statistics. More than the potential length of human life, what has changed is the infant mortality rate. It’s not necessarily that we live longer now, but that more people live to adulthood. Based partially on this misunderstanding, there are some who assert that being elderly is so horrific because we were not meant to live to 80, 90, 100. It’s not an empathetic worldview. It implies that living is not worth the cost of eventual disability. It is, though. It has to be, otherwise what are we doing here? 100 years is not a long time for the planet. It is not a long time for a Greenland shark. 100 years after birth, a Greenland shark has not yet gone through puberty.

Humans are animals that are uncomfortable with being animals. A striking feature of the culture of Silicon Valley especially, and big tech generally, is how much they hate being animals. They don’t enjoy their own meat. They do not cherish the unlikely and short life we are given. They want to be more than we are, to step beyond the hard border of the flesh. They can’t, though. No matter what technology they cobble together, no matter how closely they monitor their vitals at every moment, there is no way to escape how it will end. This is what nature is. We are mammals, warm-blooded, designed for the light and the air, warming the universe with our very existence until it drains us entirely. Greenland sharks live their long lives in the cold and the dark. You cannot have the warmth and brightness of a human life without also accepting the brevity of it.

I’ve never really understood wanting to live forever, really. I’m 29 in two weeks and already I feel ancient, as though I’ve already spent over a century in the dark water. If I was a Greenland shark, I’d still be going through puberty, so I guess not much would change there. It’s a tempting fantasy: drifting slowly in the Arctic, partially blind, knowing that I have nothing to do but move forward and eat what comes into my path. We don’t know how smart Greenland sharks are, but I would hazard a guess that a simplistic brain would be beneficial to long life. I couldn’t survive 500 years with this brain, even in the tranquility of the Arctic. I’ve barely survived 29.

There are certainly things to learn from the Greenland shark: about sustainability, both personal and ecological, and about what it takes to survive. Survival something I return to again and again. To survive the cold deep, you must slow and wait. To survive being human takes something altogether different: warmth and brightness, burning out into the universe, allowing ourselves to age and decay in the light.

OwO

While removing tiles during renovations at the Lenna of Hobart Hotel, Brian Cooper came across something hidden in the walls.

He pulled out a newspaper that was over 50 years old, but quickly realised this was no ordinary paper.

"I wasn't too sure what it was, I thought it was a porno book really," Mr Cooper said.

The 1973 erotic newspaper by Ribald in Sydney is reminiscent of a time capsule, revealing a part of Australian history almost forgotten.

Brian Cooper holding up the erotic Ribald newspaper found in the walls of the Lenna of Hobart hotel. (ABC: Eliza Kloser)

The yellowed pages feature satire articles, from a flasher with "duplicated genitalia", to a male wrestler held at gunpoint for sex.

Throughout, there are nude models, erotic comics, personal advertisements and even a sex quiz.

It also depicts photos and articles of homosexuality in a time when that was criminalised in some states and territories.

A comic section plays on 'traffic signs' with sexual innuendo. (ABC: Eliza Kloser)

Satirical and erotic articles feature throughout the Ribald newspaper. (ABC: Eliza Kloser)

Personal advertisements sent from every state in Australia featured in the paper. (ABC: Eliza Kloser)

How did it get there?

Cameron Clark's family owns the hotel, and Mr Cooper said the newspaper may have made its way there during renovations of the main mansion in 1974.

"It would have been some of the workers that were doing the renovations on it, without a doubt," he said.

"There was a can of beer next to it as well."

Historical photo of a function at the Lenna of Hobart hotel, undated. (Supplied: Lenna of Hobart)

The original 1874-built sandstone mansion is listed on the National Trust, and its walls have hosted famous guests, including Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor (the former Prince Andrew) with Sarah Ferguson, and members of the band Midnight Oil.

"[The newspaper] will probably be put into one of the scrapbooks or museum areas that we've got within the hotel," Mr Clark said.

"It's a genuine piece of history.

"But it's probably not everyone's cup of tea, so whether it will be on public display or not, I'm not sure."

The Lenna of Hobart has a rich history and is one of the original buildings near Hobart's waterfront. (ABC: Eliza Kloser)

Satire, sex and alternative press

There were several erotic and satirical newspapers in Australia in the 1960s and 70s, including Ribald, Oz, Squire, and the popular Kings Cross Whisper.

In an interview with the ABC in 1971, editor of the Kings Cross Whisper Terry Blake said it was the type of journalism people wanted compared to typical news publications.

ABC News report on Kings Cross erotic newspaper in 1971 (ABC News)

"The degree of professionalism, the degree of well-written copy and the realistic appraisal of the world as it is, [is] far more evident in the Whisper," he said.

"We publish tit pictures sure, they are pretty pictures and they are well worth looking at, but our copy is funny … our journalism is funny."

Some of the headlines featured in the Kings Cross Whisper during its publication between 1964 to the mid-1970s included:

Everything in Australia banned

Opera House to be a hamburger joint

Victoria plans new body to plan new plan

Poker machines ban people

Pop group sings in tune

So, who were the writers behind these parody articles?

Mr Blake said "some of the best journalists in Australia".

In an interview with The Sydney Morning Herald, co-creator of the Kings Cross Whisper Max Cullen said well-regarded journalists adopted fake names to write for them.

"Just about every top journo wrote for them under stupid names like 'Argus Tuft'. I called myself 'Marc Thyme'. Sounds pretty flashy, eh?"

he said.

Battle of censorship

As you can imagine, some state and territory governments at the time were not the biggest fans of these publications.

The editor of another erotic publication, called Squire, said in an interview that he received "hints" of government objection.

"We've only ever had trouble with Victoria, none of the other states have made any fuss at all," Jack de Lissa told the ABC in 1967.

"They banned nipples in colour. then they banned nipples in black and white, then they banned bottoms and then drawings of bottoms, then drawings of nipples — it just went on endlessly."

There was a legal risk involved with publishing erotic content, with the editor of the Oz, Richard Walsh, going behind bars during the 1960s, charged with issuing an obscene publication.

Some publications were also ripped off street stands in Perth by police, according to a Canberra Times article in 1973.

"Plain-clothes police raided a city bookstall today and seized sex publications valued at $500," it read.

"They took girlie magazines and copies of the eastern states publications Bawdy and Ribald."

The copy of the uncovered Ribald newspaper in Hobart shines a light on a time in Australia's media history where sexuality was scandalised.

Shame and Shamelessness: Two Sides of the Same Coin

or What Healthy Guilt Can Teach Us

There’s a pattern I see everywhere, in families, relationships, workplaces, and society, and once you see it, you can’t unsee it.

It looks like people swinging wildly between two emotional extremes:

Unaccountable shamelessness: “They deserved it.”

“I had every right.”

“I’m not the problem.”

and

Self-attacking shame: “I’m a terrible person.”

“Everyone hates me.”

“I’m the worst.”

At first glance these seem opposite.

But I’ve come to believe something different:

Shame and shamelessness are both forms of self-preoccupation - two sides which don't face each other and yet both have the same impact:

the person who was hurt is left waiting, unseen, and unrepaired.

The emotional trap: swinging from high horse to self-attack

The “shameless” version is familiar to many of us.

It’s the mode where a person:

becomes righteous

doubles down

justifies their behaviour

positions themselves as superior

blunts empathy

refuses reflection

It can even feel good, because superiority is a powerful anaesthetic.

And indignation can function like empowerment in the same way caffeine functions like energy: quick delivery, immediate force, but not lasting.

It creates havoc in relationships.

Then sometimes the pendulum swings.

The same person collapses into shame:

“I’m terrible.”

“I’m the worst.”

“Everyone hates me.”

This can give the illusion of accountability - partly because many of us have been socialised into treating self-attack as virtue. But shame collapse usually isn’t accountability. It’s still self-preoccupation, just dressed in self-criticism.

And yes, I think it’s fair to name the larger cultural influence here: in many contexts, centuries of patriarchal social conditioning have normalised emotional patterns where dominance and defensiveness are rewarded, and vulnerability becomes either performative or weaponised. In that landscape, both shamelessness and shame can become socially supported escape routes from genuine repair.

Because shame collapse can become another form of self-focus - a way of pulling the whole room back into the self, making the moment about internal pain rather than external impact.

So the swing continues:

shamelessness → shame → shamelessness → shame

And nothing actually changes.

Why both shame and shamelessness keep us stuck

Here is the thread that ties them together:

Both positions keep attention locked on “me.”

Shamelessness says: I’m fine, you’re wrong.

Shame says: I’m terrible, comfort me.

Both prevent the middle move:

Looking behind yourself and noticing the person you hurt.

That’s the real developmental leap: the ability to step out of self-preoccupation and into relational reality.

This is why words alone don’t shift patterns.

What shifts patterns is stamina: the stamina to stay present with discomfort while turning toward impact.

The middle path: Healthy guilt

There is something in the centre of shame and shamelessness that most people were never taught.

It’s not self-attack.

It’s not superiority.

It’s not avoidance.

It’s healthy guilt.

Healthy guilt sounds like:

“That wasn’t okay.”

“I can see that hurt you.”

“I want to do this differently.”

“How can I make repair?”

Healthy guilt is not identity collapse.

It’s not:

“I’m a terrible person.”

It’s:

“I did a harmful thing.”

And that distinction is everything.

Why healthy guilt matters (especially in families)

In childhood, the shame script is developmentally common.

Kids will say:

“I’m the worst!”

“Everyone hates me!”

“I’m terrible!”

This isn’t manipulation in a calculated adult way, it’s usually a nervous system trying to regulate overwhelm. It can also be mimicry depending on what they have heard others say and when.

But the risk is this:

When adults rush in and only reassure the child’s worth, without guiding repair, the child learns a bypass.

They learn that self-attack = someone else rescues them from responsibility.

Over time, this can install a pattern:

Collapse into shame to escape consequences

Swing to shamelessness to escape pain

Never build the bridge into repair

This is how it becomes intergenerational.

What does it look like to teach the middle?

The goal is not to shame children out of shame.

The goal is to teach them:

worth is stable

behaviour has impact

repair is required

and they can do it

Here are examples of what a parent (or adult) might say:

1) Hold worth steady

“You’re not a bad person. You’re safe and loved.”

2) Hold behaviour accountable

“And what you did wasn’t okay.”

3) Turn toward impact

“Let’s look at who got hurt and what they need.”

4) Make a repair plan

“What can you do to make it better?”

This is how a child learns:

guilt is tolerable

accountability is possible

relationships can survive rupture

and repair is a skill, not a personality trait

But what about adults?

Many adults never learned this.

They learned scripts that look caring but actually keep them trapped.

Examples:

quick reassurance (“No no, you’re wonderful”)

quick minimising (“It’s fine, don’t worry about it”)

quick flipping into blame (“Well you made me do it”)

quick apology that centres the apologiser (“I feel terrible”)

The hard work is not thinking about others for five seconds when you’re in a good mood.

The hard work is learning the back-and-forth movement between self and other:

self-awareness → outward attention → accountability → repair → self-compassion

That movement requires emotional maturity.

It often requires unlearning.

This is why society feels stuck

When shame and shamelessness dominate culture, we get:

moral superiority

blame spirals

humiliation as entertainment

fragile egos

performative apologies

“I’m the worst” collapse

“they deserved it” justification

And very little genuine repair.

This is why I believe healthy guilt is quietly radical: it invites accountability without annihilation

Note on originality: this framing is not new, and I’m not presenting it as a novel insight. Variations of this idea exist in attachment literature, trauma-informed relational work, and accountability frameworks. I’m sharing it here because it still isn’t widely understood in mainstream culture, and repetition across different voices and contexts matters

A closing note

If you recognise yourself in either extreme : shame collapse or shameless superiority : that doesn’t mean you’re broken.

It means you’re human.

But it may also mean you were never taught the middle path.

Healthy guilt is the place where:

you can feel proportionately bad about bad behaviour

without becoming your behaviour

while holding yourself in warm regard as a flawed human

and staying turned toward the person you hurt

That’s where repair becomes real.

And real repair is one of the most healing things humans can learn.

Australians are told every summer how hot it’s going to be.

But increasingly, the information we’re given bears little resemblance to the heat people are actually exposed to – and that disconnect is becoming dangerous.

This isn’t about climate denial or attacking science. It’s about using the right science for the right purpose, and recognising that the way we talk about heat has failed to keep pace with the conditions people now live in.

The temperature you’re told isn’t the heat you feel

When weather services report a maximum temperature – say 39 °C – many people reasonably assume that reflects what they’ll experience in their suburb, on their street, or in their home.

It doesn’t.

Official readings, such as those used by the Bureau of Meteorology, are taken under carefully controlled conditions:

- In shade

- Well ventilated

- Away from roads, buildings, cars, and concrete

- Designed for long-term consistency, not human exposure

These measurements are excellent for climate records and historical comparison. They are not designed to describe the heat load people actually endure in built-up environments.

In suburbs dominated by asphalt, brick, concrete, and dark roofs, real-world conditions can be 8–15 °C hotter than the official figure once radiant heat and stored heat are accounted for.

Yet this gap is rarely explained clearly to the public.

Why this matters more than most people realise

Heat doesn’t kill dramatically. It kills quietly.

People collapse days into heatwaves, not minutes into them. They underestimate risk because the numbers they’re given don’t match what their bodies – and their homes – are experiencing.

When a forecast says “Maximum 39° C”.

Many people hear:

- “Hot, but manageable”

- “I’ve handled this before”

- “It’ll cool down later”

But what they may actually be dealing with is:

- Street-level exposure equivalent to 45–50 °C

- Buildings that have absorbed heat all day

- Nights that don’t cool enough for the body to recover

- Cumulative heat stress across consecutive days

That mismatch delays protective action – and increases health risk, especially for older people, children, and those with chronic illness.

The missing piece: buildings don’t just get hot – they store heat

One of the most dangerous misconceptions about heat is the idea that air temperature alone determines comfort and safety.

It doesn’t.

What matters just as much is thermal mass – the ability of buildings and materials to absorb, store, and later release heat.

Brick, concrete, tiles, stone, and even plasterboard act like thermal batteries:

- They absorb heat throughout the day

- They continue releasing it long after the sun goes down

- They can keep indoor spaces hot even when outside air temperatures fall

This is why people often say, “It’s still hot inside even though it’s cooled down outside.”

They’re not imagining it. The house itself has become a heat source.

Why this changes how heatwaves should be managed

During short hot days, thermal mass can help.

During extended heatwaves, it becomes a liability.

If a building:

- Isn’t actively cooled early

- Isn’t shaded

- Has limited night purging

- Faces repeated hot days without a full cool-down

Then each day adds heat to the structure, not just the air.

By day three or four, people aren’t cooling a room – they’re trying to cool walls, floors, furniture, and ceilings that are already heat-soaked.

This is why:

- Overnight temperatures matter so much

- Consecutive days are far more dangerous than single extremes

- Homes that “cope fine” on day one can become unsafe by day four

Official forecasts rarely communicate this compounding effect.

Why “it’ll cool overnight” is no longer a safe assumption

In many heatwaves, overnight minimums stay above 22–25 °C.

That means:

- Buildings don’t fully release stored heat

- The body doesn’t fully recover

- The next day starts hotter than the last

This is one of the strongest predictors of heat-related illness and death – yet overnight risk is still downplayed compared to daytime maxima.

A house that never truly cools is not a safe refuge, even if it has air-conditioning.

“Your car thermometer is wrong” … not really

People are often told that car temperature readings are inaccurate and should be ignored.

That’s misleading.

Car sensors measure local, radiative heat exposure. They are unsuitable for climate records, but they often reflect the heat stress people actually experience at street level.

Dismissing these readings without explanation teaches people to distrust their own perception – exactly when they should be paying attention.

The data already exists – the communication doesn’t

Australia already has:

- Urban heat-island research

- Apparent temperature and heat-stress modelling

- Excess mortality data from heatwaves

- Satellite land-surface temperature data

- Health department heat-risk thresholds

What’s missing is a public-facing translation layer.

The system answers, “What is the regional reference temperature?”

People need answers to:

- How hot will my surroundings get?

- Will my house store this heat?

- Will it cool enough overnight to recover?

- How many days will this persist?

- What actions matter before the heat peaks?

Those questions are largely left to individuals to figure out – often too late.

What safer heat information would look like

We don’t need new technology. We need honest framing.

Imagine forecasts that said:

“Although the official maximum is 39 °C, built-up suburbs may experience conditions equivalent to 47–50 °C. Buildings will absorb heat throughout the day and may remain hot overnight. Actively cool living spaces early, reduce heat storage, and plan for limited overnight relief.”

That information already exists. It simply isn’t prioritised.

This isn’t alarmism – it’s accuracy

The goal isn’t to frighten people.

It’s to give them relevant, actionable information.

Australians are resourceful. When people understand how heat actually behaves – in streets, in buildings, over multiple days – they adapt.

What they can’t do is respond to danger that’s been averaged away.

As extreme heat becomes more frequent and persistent, continuing to rely on technically correct but exposure-blind temperature reporting isn’t just outdated.

It’s unsafe.

Keep Independent Journalism Alive – Support The AIMN

Dear Reader,

Since 2013, The Australian Independent Media Network has been a fearless voice for truth, giving public interest journalists a platform to hold power to account. From expert analysis on national and global events to uncovering issues that matter to you, we’re here because of your support.

Running an independent site isn’t cheap, and rising costs mean we need you now more than ever. Your donation – big or small – keeps our servers humming, our writers digging, and our stories free for all.

Join our community of truth-seekers. Donate via PayPal or credit card via the button below, or bank transfer [BSB: 062500; A/c no: 10495969] and help us keep shining a light.

With gratitude, The AIMN Team

Post Views: 364

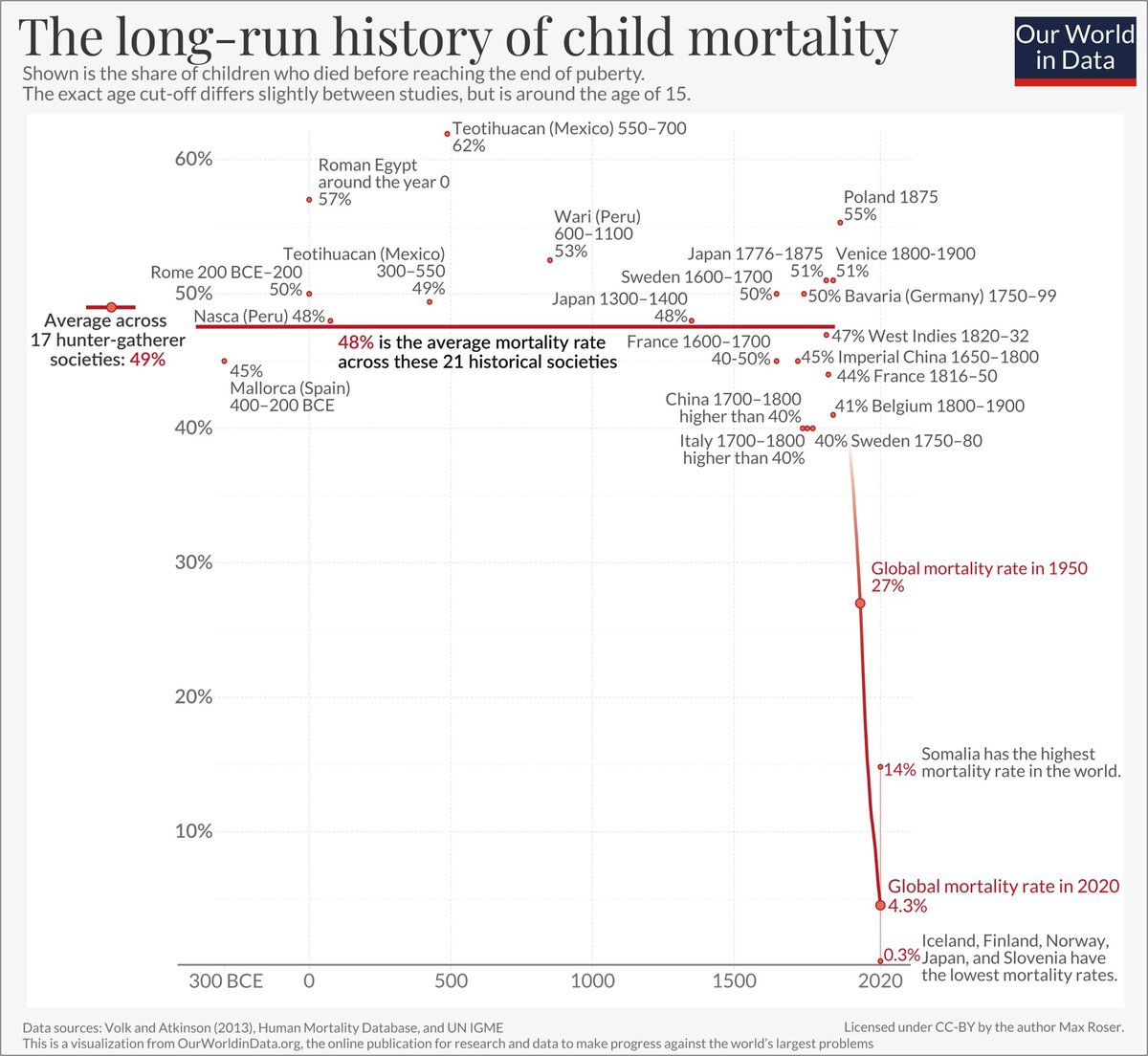

For most of human history, around 50% of children used to die before they reached the end of puberty. In 2020, that number is 4.3%. It’s 0.3% in countries like Japan & Norway.

This dramatic decline has resulted from better nutrition, clean water, sanitation, neonatal healthcare, vaccinations, medicines, and reductions in poverty, conflicts, and famine.

Before ~1800, almost every parent lost a child; now it’s such an uncommon experience that people have forgotten and want to ban vaccines.