Street Artist Eduardo Relero

“Signore Riccardo” by Eduardo Relero in Fiuggi, Italia.

More: Street Art by Eduardo Relero – A Collection

“Signore Riccardo” by Eduardo Relero in Fiuggi, Italia.

More: Street Art by Eduardo Relero – A Collection

This is America´s first Urban “Agrihood” in Detroit. It feeds 2,000 households for free from this three-acre garden and has a fruit orchard with 200 trees. It also has a sensory garden for kids.

“Over the last four years, we’ve grown from an urban garden that provides fresh produce for our residents to a diverse, agricultural campus that has helped sustain the neighborhood, attracted new residents and area investment,” said Tyson Gersh, MUFI president and co-founder.

In the spirit of recommending things I truly love, I wanted to highlight the pottery of Northern California artist Naja Tepe. I’ve ordered from her twice now, and her work is fabulous. I love her strawberry-themed items, but the crescent moon on the plate in her most recent Instagram post (upper right in the composite above) made me want to have everything it appears on, too. Great for gifts. I don’t think my mom reads this site, so I will therefore reveal that I got her a Naja Tepe item for her birthday this year.

Oh my gosh — this video about making the teeny-tiny sweaters seen in the movie Coraline! Says artist Althea Crome:

I think knitters are often fascinated by the fact that I use such tiny needles. Some of the needles are almost the dimension of a human hair.

Sublimely absurd, perfection. More info in Reactor. [Thanks, Tobias!]

And here’s another pic, grabbed from Crome’s website:

I don’t know about you, but this makes me want to drop everything and disappear into the process of knitting a microscopic sweater for the next six months. Like her Starry Night one.

Actually, the Starry Night sweater should just be its whole own post:

“I love the paradox of creating an object that takes the form of something you can wear,” Crome writes, “yet is impossible to wear.”

(Her work is also for sale.)

Tags: Althea Crome · art · Coraline · knitting · miniatures · sweaters

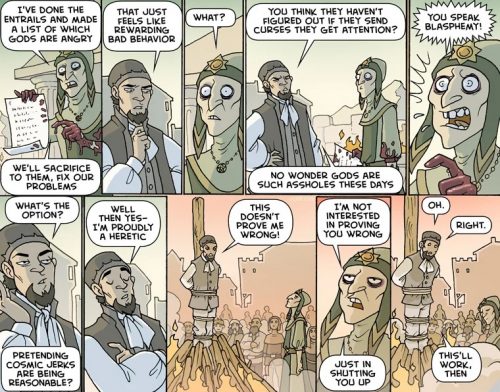

Here’s a hard-earned lesson from years of debating Christians and creationists, all summed up in one lovely cartoon.

“I’m not interested in proving you wrong. Just in shutting you up.”

Oglaf

The zealots don’t care about logic and reason, they just pretend to care, for the rubes. You’re not going to be able to logic your way past their arguments because they’re not founded on logic in the first place. Their goal is to put on a show for their fellow travelers, to distract you, and eventually, to acquire the power they need to silence you.

Don’t be like the heretic in the cartoon, only realizing their game when they’ve got you tied to the stake.

Joshua Van Dyk will happily abseil into a pitch black cave, or squeeze through crevices no one has ever gone into before.

"It feels comforting," he laughs, "I don't mind tight spots."

Although that might sound terrifying, he's had plenty of experience.

He's from a multi-generational caving family in Buchan, Victoria who have been working with palaeontologists at Museums Victoria since the 1990s to investigate caves in their local area.

And he's also part of a team of scientists, rangers and citizen cavers who recently uncovered a 50,000-year-old short-faced kangaroo skeleton in an undisturbed cave in East Gippsland.

The fossil of Simosthenurus occidentalis is one of the most complete found in Australia, and was extracted after more than 58 hours of caving in a two-year period.

"The rarity of finding a single, near complete example of an individual like this [...] it's the dream for any palaeontologist," said Tim Ziegler, Museums Victoria vertebrate palaeontology collections manager.

"The last and first time a comparably complete example of this species of kangaroo was found was in the mid-1970s. It's been nearly 50 years."

The discovery highlights the role of non-scientists in finding and extracting fossils like this — particularly recreational cavers who dig out, abseil down, and crawl through caves in their spare time.

Scientists uncovered 150 bones of the extinct kangaroo species in Nightshade Cave near Buchan.

The skeleton has 71 per cent of its bones, which makes it the most complete fossil skeleton ever discovered in a Victorian cave.

"Most of the [bones] that are missing are very small elements, like knuckles from the hands, and small bones in the feet," Mr Ziegler said.

The short-faced kangaroo specimen found by the researchers is a juvenile, but it may have weighed as much as 80 kilograms.

An adult of the ancient species would have been about the size of a large grey or red kangaroo today, but would weigh twice as much.

Researchers have suggested that this heavier structure might mean that S. occidentalis and other species of short-faced kangaroos may not have hopped, and instead walked in a similar way to humans.

"The entire skeleton — from it's shoulders and it's arms, through it's backbone to his hips and it's legs and it's tail — tells you something very different from what a living kangaroo tells you," Mr Ziegler said.

To find out the age of the specimen, the researchers sent a small sample to the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANSTO) to radiocarbon date the remains.

"We tried first to extract any collagen from the bones but we found it was quite old," said Vladimir Levchenko, a research scientist at ANSTO who dated the specimen.

"But there are other ways to date things. In particular, with this kangaroo, it was associated with a layer of charcoal. In Australia, fires are quite common, so charcoal is very present in the Australian environment."

Charcoal just above the kangaroo was found and dated, providing a minimum age for the specimen of 49,400 years old.

The fossil was first noticed in July 2011, when a group of five recreational cavers, including Mr Van Dyk, opened a cave near Buchan in East Gippsland.

According to him, the area was almost completely closed off, with "just a tiny depression and a tiny hole about the size of a 50 cent piece".

After about 20 hours of digging, the team exposed an entrance that allowed the group to abseil into the cave about 10 metres down, before belly crawling through a tight U-turn crevice into the cave.

At the time, only a small amount of the skeleton was exposed, and the remainder was under a large boulder, but the team let Museums Victoria know there was something there.

"The impression at the time was that it would be difficult, maybe impossible, to attempt the retrieval of the rest of it," Mr Ziegler said.

Being in a secluded cave, it was thought the bones would be safe from the elements, but during a follow up visit over 10 years later, the team discovered the fossil — which was not just a few bones, but an entire skeleton — had begun to decay.

"We hadn't acquired the direct dating, but we knew from national records that it had to be at least 45,000 years old," Mr Ziegler said.

"What a tragedy it would be if it had just decayed away after all of that time."

Over the next two years, Mr Ziegler worked with rangers, cavers and scientists to get into the tight spot, and painstakingly extract the skeleton piece by piece.

"Carefully cleaning and exposing bones in place, documenting, collecting samples from sediment, and individually collecting, packing and removing each element from the cave," he said.

"[You're] working at the end of your reach into this tiny little crevice. It's a very uncomfortable place to be, particularly in your all-in-one caving suit and helmets and lights.

"It was a really physically challenging process."

It's not normally scientists or museum collection managers who shimmy through caves to find bones.

Instead, it's citizen cavers, like Mr Van Dyk, who explore and chart cave systems during their spare time, mostly on weekends and days off.

"Especially with new caves, no one's ever been there before. You're the first one," he said.

"You don't know what's around the next corner, or down the next hole."

Gavin Prideaux, a palaeontology researcher at Flinders University who was not involved in the research, said cavers were "absolutely critical" to finding new fossils.

"Often times, at least in the first instance, you're relying on the people with eyes on — or under — the ground reporting finds to you, even the bad things," Professor Prideaux said.

"They're not usually in contexts where you can just casually wander in."

He suggests cavers take photos of the bones instead of touching them, as the location and surrounding area near the bones can also hold valuable information.

Most of the time the bones will likely be from a recent animal, and aren't helpful for researchers, but occasionally you strike fossil gold.

"Sometimes in cave deposits — the Naracoorte Caves are a good example — you get thousands upon thousands of bones, but it's all different individuals jumbled up," Professor Prideaux said.

While cavers are some of the few groups who have the speciality knowledge to be able to get into these difficult environments, they're not doing it for the bones.

The Victorian Speleological Association (VSA) says their aim is to "explore and chart the extensive cave systems in Victoria".

Wayne Revell, the president of the VSA, said although most scientists who need their help end up catching the caving bug themselves, they do sometimes help non-caving scientists dig out, rig up, and enter caves safely.

"A lot of cavers are volunteers and are just doing it for the fun of caving. Whether there's a paper released or not, whether it mentions the cavers or not, I don't think it's a big deal, although it might be for some," Mr Revell said.

"Tim [Ziegler] has been really good with this. He's put my name on papers and I thought, 'wow, I hardly did anything. I was just there for the enjoyment'."

As an example of a scientist who caught the caving bug, Mr Ziegler is now the vice president of the VSA.

While museum-goers are likely accustomed to seeing full skeletons of dinosaurs and ancient Australian mammals, they're not actually what they seem.

"Most fossil skeletons that are put on public display in museum galleries are replicas, and replicas are often composites," Mr Ziegler said.

This means that usually one ancient animal was not the source of all the bones in a full skeleton. Instead, multiple fossils are brought together to design one creature.

This is fine for public display, but it's not as useful for scientists, who may need to investigate how certain bones change over time or location.

Megan Jones is a PhD student looking at the vertebral column (known as the backbone) in both extinct and living species of kangaroo to better understand how they walked or hopped.

"I need to find specimens which have fairly complete vertebral columns, which the Simosthenurus occidentalis skeleton is a very good example of," Ms Jones said.

"Vertebrae are smaller bones and there's a lot of them, so the chances are they're going to get damaged."

Ms Jones also said small bones like vertebrae are sometimes not noticed among the other, more recognisable bones.

Dozens of the small bones that form the vertebral column need to be found, compared to just one easily recognisable skull.

"It's really a challenge to find good specimens," she added.

The S. occidentalis fossil will be on public display in the Research Institute Gallery at Melbourne Museum from June 24.

Get all the latest science stories from across the ABC.

Posted , updated